Evolving regulation, market structures and investor demand are shaping CRT

Credit risk transfers (CRTs) have evolved from specialty regulatory capital management tools into central components of modern balance‑sheet strategy.1 As supervisory expectations rise in some jurisdictions, capital requirements tighten and investor appetite for risk aligned exposures deepens, CRT has emerged as a pragmatic mechanism for institutions seeking to enhance capital efficiency, manage portfolio risk and sustain lending capacity without raising additional equity.

While Europe’s supervisory framework has long supported a mature and transparent market for CRT2 – also known in European countries as significant risk transfer (SRT) – recent regulatory developments in the United States are accelerating adoption and expanding the strategic relevance of these transactions. It is therefore increasingly important for issuers, investors and policymakers navigating the current capital-constrained environment to understand how CRT structures work – and why they are gaining prominence across jurisdictions.

Europe continues to account for the largest share of global CRT issuance3, supported by a longstanding and harmonized supervisory framework. Meanwhile, some U.S. banks are increasingly relying on CRT solutions for capital relief or balance‑sheet optimization as investor appetite is high and execution pathways become clearer. Together, these trends are reshaping the transatlantic landscape and elevating CRT as a strategic lever for both capital optimization and credit‑portfolio management.

Fundamental CRT Structures

There are two basic types of CRT structures, each with its own advantages:

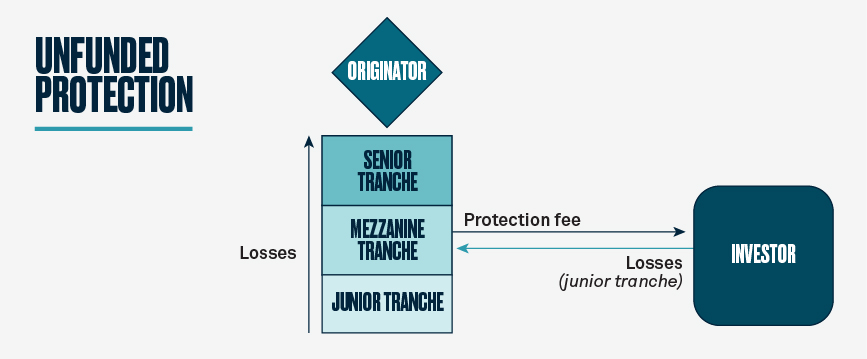

Unfunded structures

Unfunded CRT structures, typically executed through guarantees or credit default swaps (CDS), continue to play an important role in Europe4, especially when the protection seller is a highly rated institution, such as a multilateral development bank.

While these structures are well established in Europe, use of them may be constrained by a more limited investor base and reduced capital efficiency. They also introduce counterparty‑downgrade risk, which can jeopardize sustained recognition of capital relief. Nonetheless, they remain a core tool in circumstances where counterparties with strong credit profiles can deliver robust protection at competitive cost.

Unfunded structures are currently rare in the U.S. This is because the number of counterparties that can satisfy the eligibility requirements of Regulation Q for an unfunded CRT is small and unfunded CRTs result in a less favorable capital relief than fully funded structures, for which there are currently many more interested investors than issuing banks.5

Funded structures

Funded structures are a foundational component of these markets, involving upfront capital from investors through instruments such as bilateral CDS transactions and credit‑linked notes (CLNs) that are either issued by the bank itself or via special purpose vehicles (SPVs).

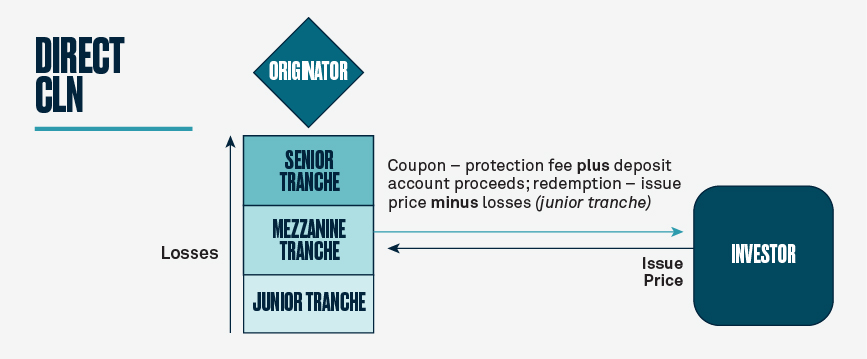

Direct credit-linked notes

Direct issuance of CLNs, without an SPV intermediation, has become increasingly common in the U.S. following Federal Reserve guidance that clarified capital‑relief eligibility for certain structures.6 In Europe, most synthetic structures are direct CLNs (both funded and unfunded).7 By removing the SPV layer, direct issuance can simplify execution and may generate tax advantages.

However, one drawback of this structure is that investors must bear the issuing bank’s credit risk directly – which generally limits the availability of this structure to highly-rated banks. Capital relief eligibility also varies by jurisdiction, underscoring the importance of regulatory alignment when structuring these transactions for cross‑border investors.

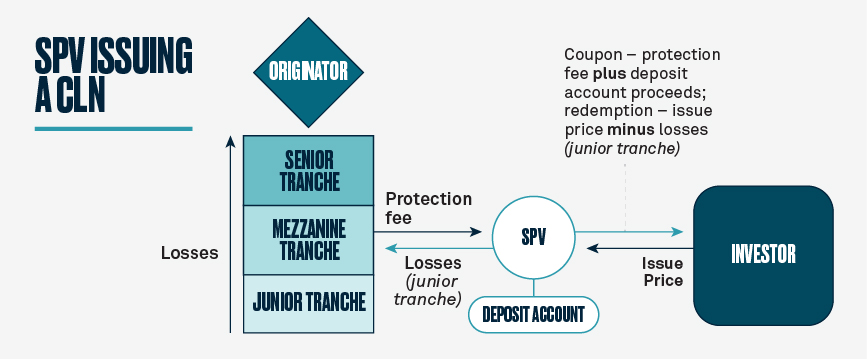

Special purpose vehicle-backed credit-linked notes

In these transactions, the originator transfers credit risk via a CDS or a financial guarantee to an SPV – which may be affiliated with the originator or could be an orphan SPV. In turn, the SPV issues CLNs to investors to finance the collateral it needs to post to the originator to support its first loss protection undertaking to the originator. This approach is widely recognized as capital‑efficient and compatible with Basel III requirements, though additional capital may be required where deposit‑bank exposure is introduced.

Regulatory Clarity: Driving CRT Developments

Europe’s regulatory environment continues to drive CRT developments. The region’s regulatory framework – including the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), European Banking Authority (EBA) guidance and the Single Supervisory Mechanism – offer transparent and harmonized requirements for achieving capital relief, addressing risk retention and meeting disclosure obligations.

In addition, recent enhancements like the European Central Bank’s streamlined fast-track review process reinforce the regulatory support for standardized structures and timely recognition of capital relief benefits. This regulatory clarity has allowed Europe to maintain its leadership position in the market.8

Although it has historically been a smaller market, the U.S. is gaining momentum. The Federal Reserve and Commodity Futures Trading Commission have eased execution constraints for synthetic transactions. “Recent U.S. regulatory developments – particularly CFTC no-action relief and a likely retreat from more punitive capital parameters – are helping to clear longstanding execution hurdles for bank-led CRT,” said Matthew Bisanz, a partner at Mayer Brown, LLP.

Furthermore, capital requirements continue to evolve and lending demand has been robust. As a result, the U.S. is seeing increased use of CRT among institutions looking for balance-sheet flexibility without credit supply constraints. According to Sagi Tamir, a partner at Mayer Brown LLP, “An impactful clarification by U.S. regulators that would fuel further growth in the U.S. CRT market is to either eliminate the $20 billion cap for direct-issued CLNs or move away from the existing one-cap-fits-all limit to different caps for different categories of financial institutions, where each cap is commensurate to the category of financial institutions to which is applies.”

Ensuring a Successful CRT Strategy

Realizing the full potential of CRT markets will require ongoing investment in data systems, modeling capabilities and specialized structuring expertise. Robust issuer‑investor partnerships will remain essential, particularly as investors increasingly scrutinize collateral quality, model transparency and risk‑alignment mechanisms. Policymakers will also shape market evolution through their emphasis on transparency, consistency and prudential safeguards – elements critical to maintaining systemic resilience while enabling innovation.

Trustees and agents like BNY that have substantial CRT experience can bolster the stability of these transactions by providing transparent reporting, consistent administration and independent oversight. Their familiarity with collateral processes, covenant mechanics and evolving regulatory expectations can help ensure structures operate consistently and predictably – an increasingly important topic for regulators, investors and issuers. In a market shaped by cross-jurisdictional nuances and rising demands for clarity, this steady operational footing supports confidence by doing the essential work well.

Sources

1 McKinsey, “Risk Transfer: A Growing Strategic Imperative for Banks,” 2025. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/risk-transfer-a-growing-strategic-imperative-for-banks

2 Mayer, Brown. “Synthetic Risk Transfer (SRT) in 2025” (2025). https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/insights/publications/2025/05/synthetic-risk-transfer-srt-in-2025

3 McKinsey, “Risk Transfer: A Growing Strategic Imperative for Banks.”

4 Mayer, Brown, “Synthetic Risk Transfer (SRT) in 2025.”

5 Managed Funds Association, “Primer: Introduction to Significant Risk Transfers.” https://www.mfaalts.org/industry-research/primer-introduction-to-significant-risk-transfers

6 Managed Funds Association, “Primer: Introduction to Significant Risk Transfers.”

7 Mayer, Brown, “Synthetic Risk Transfer (SRT) in 2025.” 8 Mayer, Brown, “Synthetic Risk Transfer (SRT) in 2025.”

Disclaimer

BNY is the corporate brand of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation and may be used to reference the corporation as a whole and/or its various subsidiaries generally. This material and any products and services mentioned may be issued or provided in various countries by duly authorized and regulated subsidiaries, affiliates, and joint ventures of BNY. This material does not constitute a recommendation by BNY of any kind. The information herein is not intended to provide tax, legal, investment, accounting, financial or other professional advice on any matter, and should not be used or relied upon as such. The views expressed within this material are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of BNY. BNY has not independently verified the information contained in this material and makes no representation as to the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, merchantability or fitness for a specific purpose of the information provided in this material. BNY assumes no direct or consequential liability for any errors in or reliance upon this material.

This material may not be reproduced or disseminated in any form without the express prior written permission of BNY. BNY will not be responsible for updating any information contained within this material and opinions and information contained herein are subject to change without notice. Trademarks, service marks, logos and other intellectual property marks belong to their respective owners.

© 2026 BNY. All rights reserved. Member FDIC.