Cathy Braganza, senior portfolio manager at Insight Investment1, explains why tightening spreads with high yields create a potentially attractive risk-return balance for credit investors.

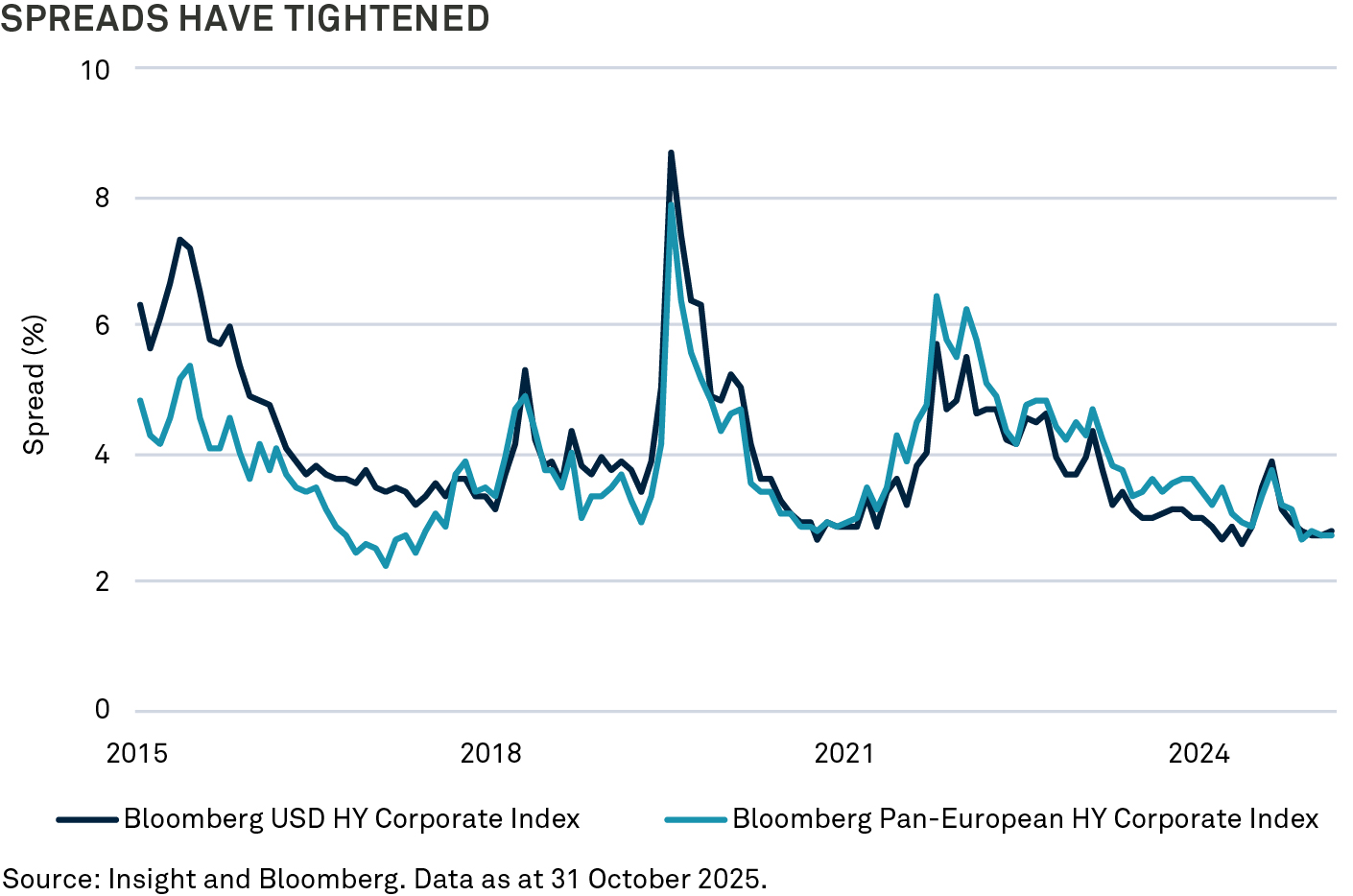

Credit investors face a market where spreads are tight, but yields are historically high.

In fact, in high-yield markets, spreads have arguably narrowed to reflect the improving quality of issuers within the market.

The average rating in the market today is BB – just a notch below investment grade – making historical spread comparisons less meaningful.

With many BB-rated companies showing credit metrics comparable to – or in some cases stronger than – their investment-grade peers, the probability of default has significantly decreased.

As a result, we believe the current level of spreads often reflects a fair compensation for the risk taken rather than a result of excessive tightening.

Importantly, despite narrower spreads, absolute yields are still attractive, which we believe offers investors a compelling balance of risk and return.

The structural transformation of high yield

We believe the structural change to high-yield credit helps explain why spreads are tighter than in the past.

High-yield issuers have shown resilience during economic slowdowns, supported by better credit quality and persistently low default rates.

Based on current market conditions, we believe these trends are likely to reinforce demand in the credit market, unless there is a major recession or systemic crisis.

Over the past few decades, the high-yield market has persevered through multiple crises like the 2008 global financial crisis, the pandemic, and the recent surge in interest rates.

Those big events taught issuers to strengthen their governance and improve their financial discipline. Management teams are now more likely to focus on well-defined growth plans, securing funding certainty, and protecting their operations from market volatility.

The pandemic reinforced this way of thinking, and we do not see it changing – at least not for the foreseeable future.

Companies have become better at managing their maturity profiles, too, often refinancing well ahead of schedule. This reduces refinancing risk and benefits investors with early bond calls at a premium. Refinancing now dominates primary issuance.

The rise of private credit has further reshaped the high yield landscape. Once the main source of defaults, smaller or more distressed issuers are increasingly turning to private markets where bespoke financing and restructuring flexibility are more readily available. This migration has led to a marked improvement in the overall credit quality of the public high yield universe.

For example, BB-rated issuers make up over 54% of the US high yield market as of October 2025 (see Figure 3) – that’s up from 35% in 1999.

This has coincided with lower defaults. The 12-month rolling default rate is just 1.1% in the US and 1.6% globally (see Figure 4) – well below the long-term average of 3.4%.

A wall of cash could move into bond markets

The past few years have seen a dramatic change in investor behaviour as central banks normalised interest rates to combat post-pandemic inflation. When cash rates soared, retail and institutional investors flocked to money market funds (MMFs), which offered high yields with minimal risk and deep liquidity.

US MMF assets were steady at around $3 trillion for years after the global financial crisis, but by mid-2025 they reached $7.4 trillion – up $2.3 trillion since the Federal Reserve began hiking rates in early 2022 (see Figure 5).

In the UK, cash ISAs saw record inflows of £47.2 billion in 20232– more than the previous eight years combined.

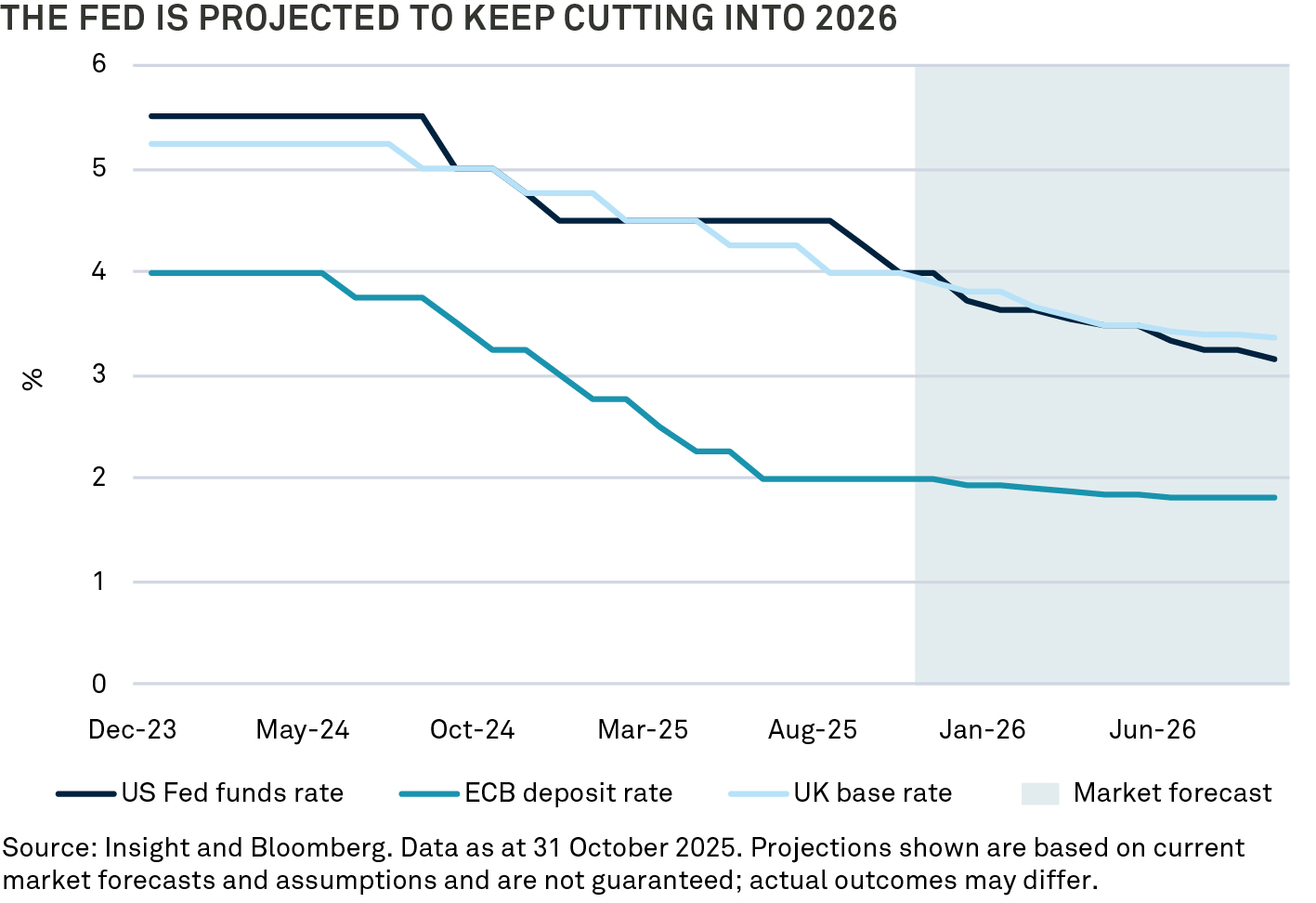

More recently, central bank policy has diverged. The European Central Bank has eased more aggressively than other developed-market peers, although we expect the Federal Reserve to close the gap in 2026. As cash rates decline and yield curves steepen, we also expect investors to move out of cash, which could release significant liquidity into credit markets.

High-yield credit in a low-growth environment

We don’t expect a global recession, but we expect economies to remain sluggish. That does not have to be a problem for credit markets, though, as long as nominal growth stays positive.

A slow economy can challenge equities, as it implies that profit growth rates will be hard to maintain organically. For fixed income investors, however, the key is reliable debt repayment and not rapid growth. Even modest nominal growth can support credit returns.

Historically, when growth has ranged between 0% and 2%, credit – especially high yield – has tended to perform well (see Figure 7).

Active credit managers have considerable potential to add value beyond benchmark yields. Fixed income markets are structurally less efficient and transparent than equities, but that gives skilled managers extra room to find mispriced assets and inefficiencies. And the rise of passive strategies has, if anything, only widened these distortions.

Credit markets also create openings for relative value and roll-down strategies. So, it is essential to look past headline yields and look for managers with a consistent record of outperforming their benchmarks.

The value of investments can fall. Investors may not get back the amount invested. Income from investments may vary and is not guaranteed.

1Investment Managers are appointed by BNY Mellon Investment Management EMEA Limited (BNYMIM EMEA), BNY Mellon Fund Management (Luxembourg) S.A. (BNY MFML) or affiliated fund operating companies to undertake portfolio management activities in relation to contracts for products and services entered into by clients with BNYMIM EMEA, BNY MFML or the BNY Mellon funds.

2Investment Management in the UK 2023-2024.pdf, (PDF), October 2024, Investment Association

2872559 Exp: 5 June 2026