Walter Scott1 client investment manager Murdo MacLean argues it is likely that valuations have taken the shine off some US companies. So, what does the future hold for US exceptionalism – and what type of companies and sectors are best placed to stand the test of time?

Key points

- US equity market volatility reflects concerns over durability of US leadership and uncertain domestic policy agenda, shifting global leadership as the rest of world gains prominence beyond the tech giants.

- Market concentration rarely lasts, and portfolio construction should focus on durable growth and valuation rather than current index leaders.

- With deglobalisation and US reshoring efforts creating supply chain challenges and volatility, companies with global footprints and pricing power should be better positioned.

- Healthcare offers structural growth opportunities, with Walter Scott tending to favour medical devices over drugs due to lower pricing risk.

- Consumer discretionary stocks with strong brands and defensive qualities could provide resilience amid economic uncertainty and potential recession.

The US grip on global equity markets appears to be slipping precisely at a time when the country’s administration is focused on reshoring, notes Walter Scott’s Murdo MacLean. This dynamic is amplifying global supply chain and trade volatility but companies with durable growth, strong balance sheets and asset light business models are well positioned to weather the turmoil, he argues.

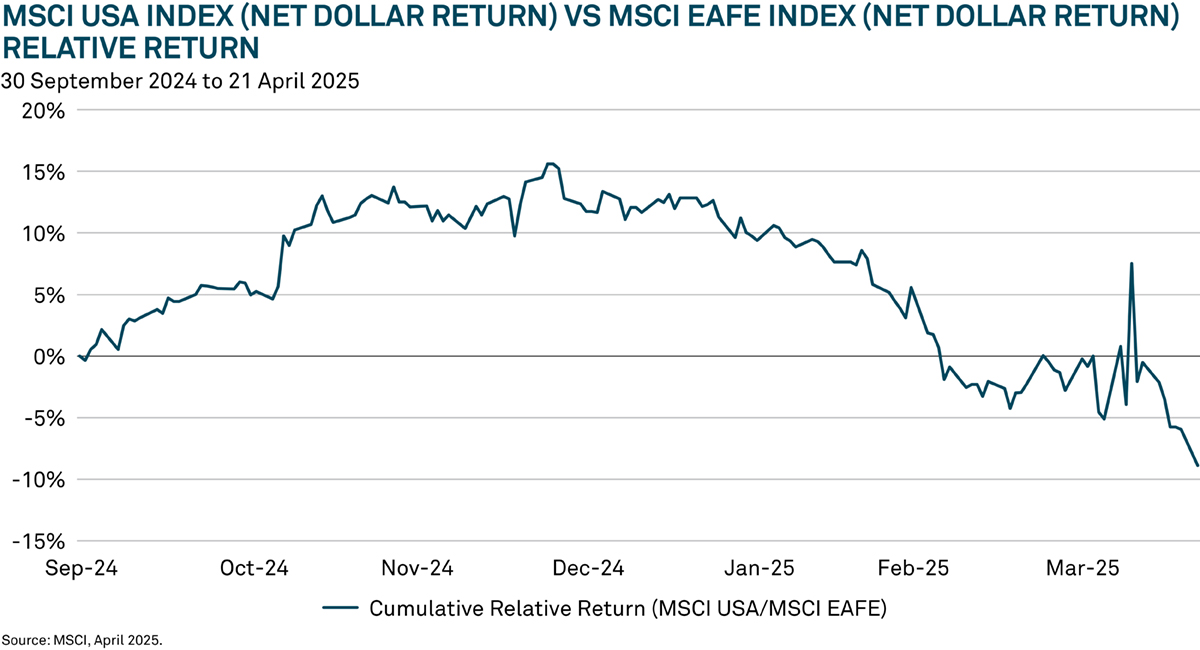

After a stellar run in recent years, the US equity market had a bumpy first quarter. In fact, it was the MSCI USA Index’s worst quarter in 30 years compared with the rest of the world, as measured by the MSCI EAFE Index (see chart below).

Last year, a handful of US stocks – the so-called Magnificent Seven – led global markets. Those names accounted for some 48% of the MSCI World Index’s total return in 20242. But a look at this year so far shows the rest of the world has gained some of this share.

Looking at performance over one year to 31 March 2025, the Magnificent Seven accounted for 37% of the return but the remainder, almost two-thirds (63%), came from names in the rest of the MSCI World Index3.

Market concentration rarely lasts

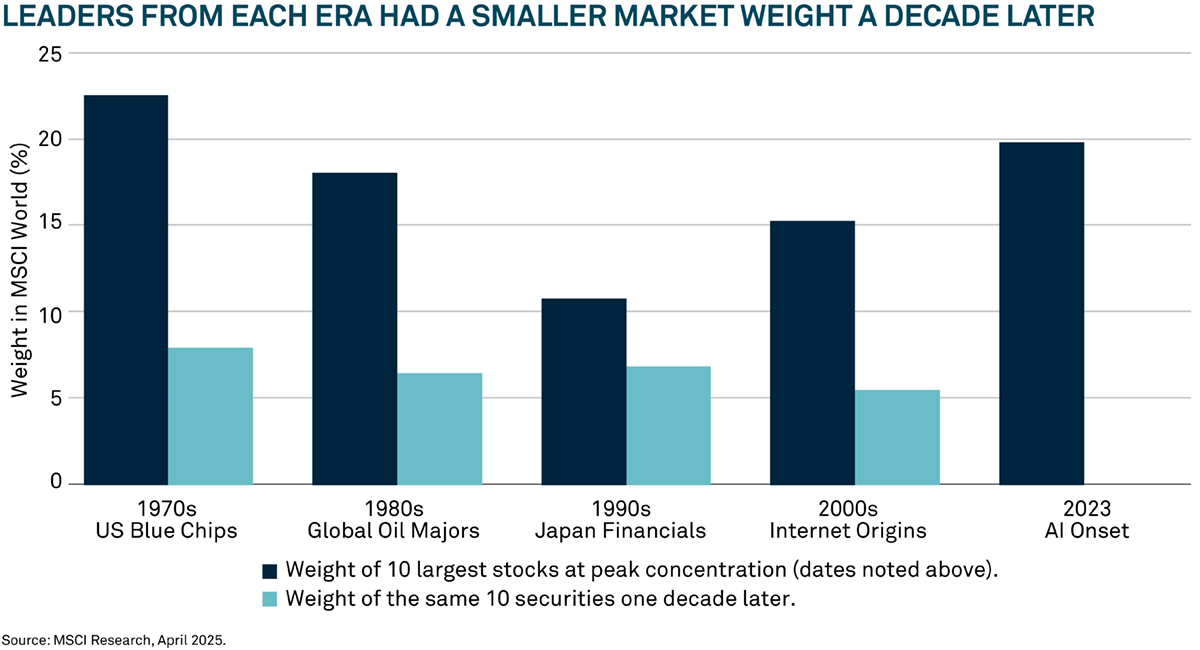

MacLean says a lot of people are now asking whether US dominance will continue. Of course, no one knows, he adds, but what can be gleaned from looking at history is that episodes of market concentration rarely last. In other words, companies at the top of the tree don’t stay there forever.

In fact, in each of the previous four decades, the leading companies fell away in the following decade, whether it was US blue chips in the 1970s, oil majors in the 80s or Japanese financials in the 90s (see chart below). Since 2023, artificial intelligence-driven tech has been on top but what about the next decade?

“We have no idea what 2033, 2043 is going to look like but there is a good chance it won’t look identical to today,” says MacLean. “So, we are constructing a portfolio for the next 10 years rather than replicating the index today. If you had done that in any of these prior decades, it might have been a poor strategy for portfolio construction.”

Valuation is key

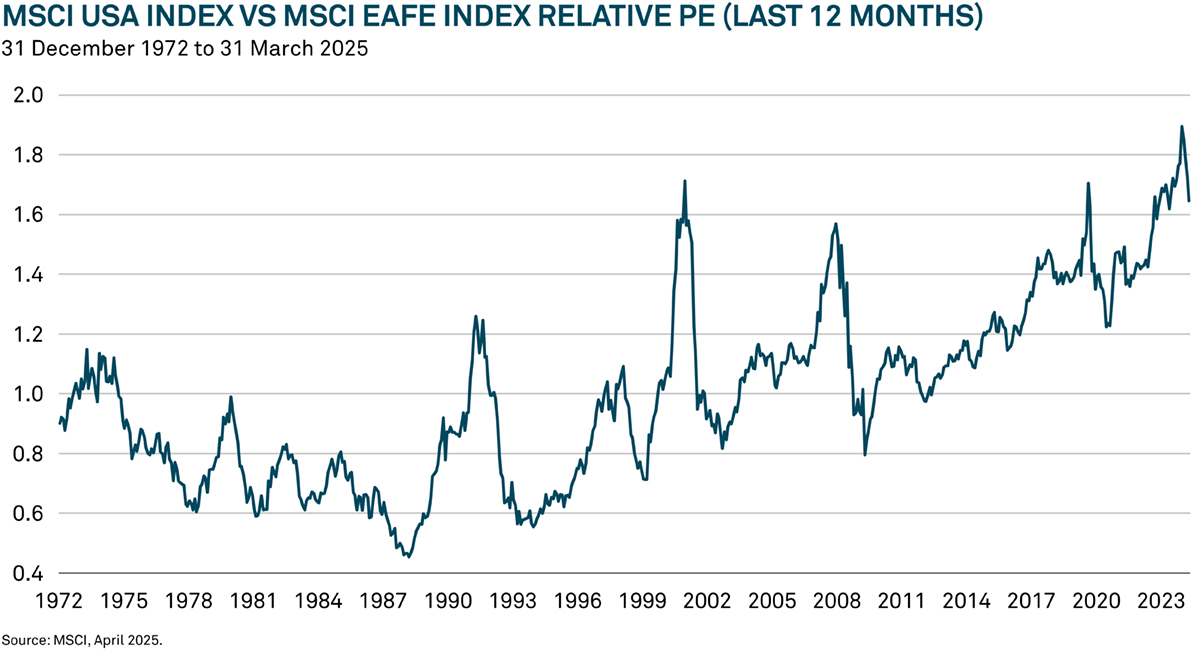

Ultimately, says MacLean, valuations will dictate whether US exceptionalism will continue. He suggests the recent change in fortune for US stocks is related to investors’ perception of valuations, as opposed to Europe suddenly looking fantastically attractive thanks to its defence and infrastructure spending and a broadening of its trade lens.

The US has historically traded at a premium that has been growing over the years (see chart below). But, adds MacLean, these stocks have been propelled by cheap interest rates and impressive growth from tech. “If you overpay for something it doesn’t matter how good the business is, it is unlikely to result in being a good investment,” says MacLean.

Valuation has been key as to why Walter Scott has not owned all the Magnificent Seven in portfolios. But the cheaper the US gets relative to international markets, the more interesting the region potentially becomes, posits MacLean.

Deglobalisation challenges

The rise of protectionism is challenging globalisation, says MacLean. The US is focused on bringing manufacturing and jobs back to the US. “That is perhaps an exciting prospect if you are in the US but in reality, I don’t believe there will be a large-scale movement of supply chains,” he adds.

Granted, it is possible to see companies increase spending in the US, says MacLean, but a lot of it could be just enough to appease the US government rather than resulting in a wholesale shift of supply chains back to the US.

MacLean believes trade and supply chain disruption will take a long time to settle and is likely to create a lot of volatility and challenges for companies (see box out). To prepare for such an environment, Walter Scott focuses on businesses with global footprints that sell products and services that command significant pricing power.

“When you go through periods of challenge, the one thing these companies can count on is that customers still require their products and services,” he adds. “There are potentially a lot of casualties in this new world order that don’t have that pricing power.”

The core of the issue

Apple’s globalised supply chain:

- Apple makes about 230 million iPhones a year, which equates to 438 per minute3.

- Each phone has 2,700 parts for which Apple relies on 187 suppliers across 28 countries4.

- Some 150 of those suppliers in 2024 had factories in China5.

- Less than 5% of iPhone components are made in the US6.

- The iPhone has 74 tiny screws all fitted by hand in China and India7.

- Apple earns about US$400 for an iPhone16 Pro (256GB). Assembly and testing costs US$10, batteries US$4, display and touch screens about US$388.

- The US relies on China for 70% of rare earths9 which are crucial to the phone’s vibration, colour screen and batteries.

- iPhones made in the US would likely cost more than three times their current price of around US$1,00010.

“It is clearly one of the most globalised supply chains. It is a massive challenge, so I think there will be a lot of negotiations,” says MacLean. “It is no surprise that Trump came out and said smart phones were exempt from tariffs11.”

Healthcare

MacLean says healthcare is enjoying obvious structural growth tailwinds. The sector has performed poorly in the past five years, largely due to the lingering effects of the global pandemic, but Walter Scott believes the cyclical pressure will abate.

MacLean observes two key diseases likely to drive healthcare innovation: obesity and cancer. “The obesity market is huge, we have barely scratched the surface,” he adds. “Companies at the forefront of this stand to do well.” Elsewhere, MacLean notes there are more people living with cancer. In the UK alone, the number is expected to rise from 3.5 million today to 5.3 million by 204012.

“There will be drugs that do very well but typically our exposure is more focused on medical devices because with devices there is less volatility and sensitivity on pricing, and it tends to be less politicised.”

MacLean flags Swiss CDMO (contract development and manufacturing organisation), Lonza, which is used by pharmaceuticals to manufacture their drugs and get them approved by regulators.

“Whenever a drug company is doing well, technically Lonza should benefit,” says MacLean. “It does not face the same challenges as pharmaceutical companies such as patent-cliff anxiety, or drugs failing in the late stages.”

Additionally, notes MacLean, Lonza does not directly export anything – it delivers the drugs to the gate of the customer who is then responsible for distributing them. So, from a tariff perspective it is in a good place.

Consumer discretionary

MacLean says the consumer discretionary sector can bring defensive attributes to a portfolio. This is because strong players in the space either tend to benefit when consumers are tightening their belt or have the brand strength that makes them desirable when consumers are feeling the pinch.

He highlights two companies in this space: O’Reilly Automotive and TJX.

O’Reilly Automotive is one of two dominant players in the US auto parts retail market. It is a market consolidator in a fragmented industry which puts it in a strong position, MacLean says. Americans love their cars and in a struggling economy, people are more likely to repair their cars than buy new ones. The average age of a vehicle in the US is about 13 years13 which bodes well for O’Reilly Automotive’s sale of parts and accessories.

The company is US focused so it imports only a small quantity of items, making it well positioned for any tariff turmoil.

Elsewhere, MacLean flags TJX, owner of discount clothing retailer TK Maxx, as a world leader in off price apparel and home fashion. It has a unique sourcing model that involves buying excess inventory from brands and selling them at a discount. The result is a “treasure hunt-type experience” which creates a sense of urgency among shoppers – once an item is gone, it’s gone. “It is continually a new experience for the consumer,” says MacLean.

“People trade down to TJX during recessions and tend to stay when they realise the cost savings,” he adds. “Long-term growth is driven by market share gains from traditional department stores, growth in the homeware categories space and further international expansion.”

Looking ahead

With supply chain disruption in motion and economic growth under threat in major economies, there is a chance of recession, notes MacLean. But, he adds, Walter Scott believes companies that are highly profitable, have durable growth, strong balance sheets and are asset light, tend to do better over the long term than the average company.

“When we have periods of lower economic growth, although these companies might see their earnings growth slow, they also tend to gather market share from competitors. So, they tend to come out the other side having done better than their peers and setting themselves up for the next leg of growth,” he concludes.

The value of investments can fall. Investors may not get back the amount invested.

1Investment Managers are appointed by BNY Mellon Investment Management EMEA Limited (BNYMIM EMEA), BNY Mellon Fund Management (Luxembourg) S.A. (BNY MFML) or affiliated fund operating companies to undertake portfolio management activities in relation to contracts for products and services entered into by clients with BNYMIM EMEA, BNY MFML or the BNY Mellon funds.

2Source: Walter Scott, MSCI and Factset April 2025. Magnificent Seven = Nvidia, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, and Tesla.

3Ibid.

4FT. Apple aims to source all US iPhones from India in pivot away from China. 25 April 2025.

5FT. Why Trump can’t build iPhones in the US. 28 April 2025. 18 April 2025.

6BBC. Designed in US, made in China: Why Apple is stuck.

7FT. Why Trump can’t build iPhones in the US. 28 April 2025. 18 April 2025.

8Ibid.

9Ibid.

10BBC. Why China curbing rare earth exports is a blow to the US. 17 April 2025.

11CNN Business. iPhone could triple in price to $3,500 if they’re made in the US, analyst warn. 23 May 2025.

12BBC. Trump exempts smartphones and computers from new tariffs. 12 April 2025.

13Macmillan Cancer Support, https://www.macmillan.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/research/cancer-prevalence#355989, April 2025

14spglobal.com. Average age of new vehicles hits new record in 2024. 22 May 2024.

2502109 Exp: 19 December 2025